A borderless world

in CinemaScope

Despite ham-handed censorship by political curmudgeons, cinema is bringing Asia closer together. Can cultural diplomacy survive?

By ROSHNI MULCHANDANI

Hong Kong, April 2013

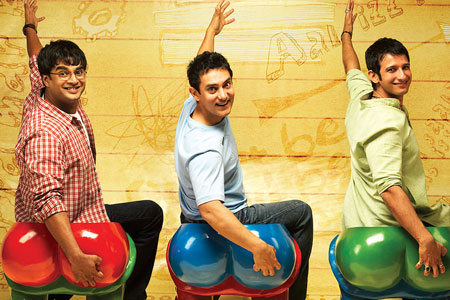

3 Idiots took Asia by storm, reaching some surprising corners, with a heart-warming universal tale of student suffering and triumph.

WHEN 3 Idiots managed to break box office records in India, no one was surprised. After all, it packed in all the ingredients for a hit film: Aamir Khan (India’s most sought after actor), Rajkumar Hirani (a hit producing film director), an innovative plot derived loosely from a popular English novel by an Indian author, and cheerful sing-along music. However, it was only when the film went on to gain acclaim in the United States, Australia, Africa and even China, that film pundits realised it's true impact.

Indian films have long been recognised as odd and old school. The idea of a film stretching three hours or more and filled with song and dance tedium tended to put off international audiences who found it all endearing but not compelling. It was only after the Oscar winning British film Slumdog Millionaire, which released in 2008, a year before 3 Idiots, that cinemagoers got a taste of new wave Hindi cinema. While the Oscar winner was not from India, its nuances and sensibilities had firm roots in Indian cinema.

Roshni Mulchandani

They laughed and chatted happily about the film and, as my pedicurist painted my toes, she sang along to the title track. The irony was delicious: an Indian getting a pedicure in Hong Kong by a Chinese lady watching a dubbed Hindi movie

Late last year as I frantically rushed for my monthly pedicure, I walked into my regular Hong Kong spa to the opening credits of 3 Idiots. Local patrons appeared mesmerised. They laughed and chatted happily about the film and, as my pedicurist painted my toes, she sang along to the title track. The irony was delicious: an Indian getting a pedicure in Hong Kong by a Chinese lady watching a dubbed Hindi movie. Right there, at that moment, a cultural intersection had presented itself. The power of cinema to cross borders and boundaries was immediately evident.

It mattered not a whit that the characters weren’t Chinese; nor the locales or even the cultural references. But the metaphors were universal – the harsh and rigid education system, so similar to what Chinese in Hong Kong and the mainland are subjected to. This was enough for any Hong Kong movie fan to watch the film not once but in many instances twice and thrice. Chinese film experts were fascinated by how audiences took to the film in a span of just two weeks especially since foreign films run under a quota system in which only 20 international films are screened. In China alone, box office collections amounted to US$2 million over a span of only 18 days.

Interestingly, the acceptance of 3 Idiots in China shows a shift in the otherwise conservative Chinese mentality. Even though the Communist government controls all aspects of the nation’s cultural activities, including social media, the internet and cinema, and insists on holding tightly to its conservative traditions so that foreign influence is minimised, a Hindi film still managed to create waves.

Hollywood too sees the growing influence of its films in China. Demand is high but it loses a fortune each year due to piracy. This sharply underlines how cinema is affected by a perceived cultural or political divide. The idea that the West is far too undisciplined in its social values and core belief system is one that many Asian countries drill into their populations. Conservatives who believe the West is hell bent on westernising their nations, are determined to keep anything associated with it well away. And this isn’t just a Chinese worry; it’s a cause for concern in many other Asian countries who insist on blocking sex, violence and "modern" ideas in order to preserve "traditional" values.

However, if we take a look at younger Asian films, it is easy to see that most can hardly be described as squeaky clean anymore. In the last decade, a major shift has been seen in filmmaking and the stories that are told. No more are Asian filmmakers worried about pushing the envelope too far. In fact, they are willing to take a plunge and tell stories about social transition and transformation.

Indian cinema has seen a paradigm shift. Amidst the candy floss and family drama that dominates television serials, younger filmmakers are working with casts from different walks of life and producing films about incest, sperm donation, sex trafficking and showcasing the real life of the "rich and famous". Japanese cinema, which is known for being dark and edgy, has become lighter hearted as filmmakers recognise the need to go uptempo in a country emerging from various traumas spanning earthquakes, tsunamis and nuclear radiation.

As time moves on, we can expect more films that bring countries and cultures together simply because of increasingly educated audiences and collaborative cinema. Major western production houses are popping up in various countries and buying stakes in international films. Their interest in Asian cinema is keen and they are aware of its growing market. With a globalised world getting smaller, cultures are intermeshing even more. Thus there is more awareness of various types of cinema and growing acceptance on all levels.

Films like Titanic and the James Bond testosterone romps have had a number of scenes edited out from the Asian versions. Kate Winslet's bared breasts and Javier Bardem’s torture scenes set in a Chinese prison were thus quickly chopped at the editing table

Hollywood now finds itself in a rather interesting spot. Since the arrival of modern and experimental cinema from the East, filmmakers have been looking at ways in which they can marry ideologies into a workable blend as the Asian market is the second biggest box office worldwide. Producers have altered films and plots to make them more engaging to filmgoers across Asia. They have had to keep in mind the fact that while they are still working with a contemporary audiences, they still have to deal with traditional governments. It is a delicate balancing act.

Films like Titanic and the James Bond testosterone romps have had a number of scenes edited out from the Asian versions. Kate Winslet's bared breasts and Javier Bardem’s torture scenes set in a Chinese prison were thus quickly chopped at the editing table. In fact, the Chinese censor boards come down so hard on anti-Chinese plots and characters that in a number of instances filmmakers have had to change scenes, names and national flags to be allowed in. In the West where films are viewed more as entertainment there is less room for propaganda.

Asian cinema has developed a strong niche for itself. Each country has excelled in a certain genre mastered over time. Indian cinema has surpassed a century now and has changed dramatically in its sensibilities. While this is due to globalisation over the last decade, it also has much to do with the changes in audience attitudes. Indian audiences are no longer interested in cinema which is a replica of their lives – family dramas, poverty, corruption and struggles. They look for escapism in their films with hints of reality. We see this in small changes that are slowly taking over Hindi cinema. Tighter scripts have been edited down to two-and-a-half hours. Song and dance numbers have been cut down, sometimes eliminated; a sea change for Hindi movies where this was the norm if not the main purpose.

The West continues to be mimicked in Asia. Every nation, it seems, has a director that apes one from the west with Quentin Tarantino being the most copied in terms of style and film technique. But an Indian Tarantino like Anurag Kashyap does not make films that moviegoers cannot comprehend; quite the opposite, in fact. Using Tarantino’s techniques, Kashyap has made a number of films which are similar in presentation and delivery, yet very Indian in appeal, and very mass oriented.

International collaborations and actors crossing borders is now common. Gone are the days where Jackie Chan was the only Asian face at an award ceremony – now it is quite usual to see the likes of Brad Pitt conversing with an Indian, Japanese and even a South Korean superstar on the red carpet.

As audiences come closer, even the biggest celebrities still goof up on occasion. Oprah Winfrey found herself in a pickle after she took her travel show to India and commented, ‘'I heard some Indian people eat with their hands still." This created a furore and Oprah was rightly flayed for her ignorance. As one Indian journalist fumed, "Using our hands to eat is a well-established tradition and a fact none of us are ashamed of. Our economic distinction has nothing to do with it. A millionaire here eats the same way a pauper does."

Cinema is a powerful tool for cultural integration using universal metaphors that resonate. A classic example is Canadian author Yann Martel's Life of Pi about an Indian boy from Pondicherry – shipwrecked with a Bengal tiger for company – brilliantly brought to the big screen by the cinematic pyrotechnics of Taiwanese director Ang Lee. Film certainly has an impact on politics and economics too. But whether it continues to serve – or is permitted to function – as an agent of positive change and emotional or political liberation, remains to be seen.

After a decade in the United States, having worked as an editor for an online entertainment web magazine and as a freewheeling a lifestyle and fashion writer, Roshni Mulchandani has been based in Hong Kong since early 2013. When not penning her blog or working on other writing, Roshni keeps busy with social media and long walks.

Post a comment

- HOME

- BUSINESS

- DEVELOPMENT

- ENERGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- HEALTH

- INFORMATION

- POLITICS

- SECURITY

- SHIPPING

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- TRENDS

Long term impact of Gaza attack on Israel

Consequences of Palestinian conflict and finger-pointing in the blame game ... See world opinion

Curse of curation

PR-speak is turning our conversations into outright gibberish... more…