In India, God talks to everyone

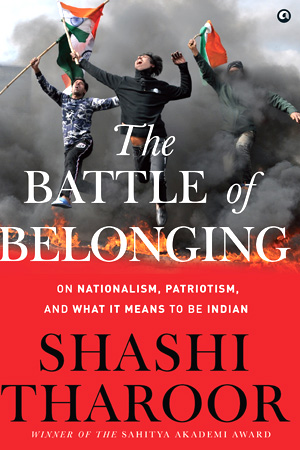

An essay in diversity and the essence of India, the following is a chapter from a new book, 'The Battle of Belonging' (Aleph Book Company), by Shashi Tharoor.

By SHASHI THAROOR

NEW DELHI, November 2020

Congress parliamentarian, novelist and political commentator, Shashi Tharoor, takes a closer look at his India and the immense diversity that has been a source of strength and inspiration for the country. From his youth in Kolkata (Bengal) to his parliamentary stewardship of Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala), this is a story redolent of prayers and politics; of history and histrionics; of incense-wreathed temples, mosques, gurdwaras and churches, where God talks to everyone. The 22 languages and 20,000 dialects are all strands of a common, intricately woven, tapestry. 'The challenge of defining India is immense,' writes Tharoor.

IN a world where nationality and nationalism were deemed to be special virtues in a people,’ Dr B. R. Ambedkar observed somewhat tartly in 1940, ‘it was quite natural for the Hindus to feel, to use the language of Mr H. G. Wells, that it would be as improper for India to be without a nationality as it would be for a man to be without his clothes in a crowded assembly.’139 That sardonic comment by the man who would chair the Drafting Committee of India’s Constitution, and be known in the West as India’s James Madison (the principal draftsman of his country’s Constitution), was not intended to be taken as a dismissal of the idea of Indian nationalism. Rather it was his way of questioning the existing underpinnings of that idea, especially in the context of the challenge that had arisen to it with the demand of the Muslim League for the partition of the country.

Shashi Tharoor

‘India,’ Winston Churchill once snarled, ‘is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a single country than the Equator.’

The ‘idea of India’—a phrase (even a cliché) that I evoked in the preface to this book—has become a highly contested concept these days. But I cited it secure in the conviction that the idea of India, though the phrase is Tagore’s, and so hardly recent, is, in some form or another, an even older aspiration for cultural unity that appears throughout the history of our civilization, and is arguably as old as antiquity itself. When, in explaining my choice of nationality, I had said to that British consular official, ‘I look in the mirror and I see an Indian’, I seemed to be implying an ethnic basis for my nationhood. But that was never the whole story: while I had studied the anti-colonial nationalism that had catalysed and driven the Indian freedom struggle, and written about the civic nationalism enshrined in its Constitution, I was reflecting a far deeper sense of what being Indian meant.

At midnight on 15 August 1947, independent India was born as its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, proclaimed ‘a tryst with destiny…a moment…which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.’ With those words he launched India on a remarkable journey—remarkable because it was happening at all.

‘India,’ Winston Churchill once snarled, ‘is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a single country than the Equator.’ Although Churchill was often wrong about many things, it is true that no other country in the world embraces the extraordinary mixture of ethnic groups, profusion of mutually incomprehensible languages, varieties of topography and climate, diversity of religions and cultural practices, and range of levels of economic development that India does.

And yet India, as I have repeatedly said, is more than the sum of its contradictions. Those contradictions were repeatedly stressed by British rulers in self-justification for their rule. Thus Benjamin Disraeli (who memorably said that ‘a nation is a work of art and a work of time’, gradually created by a variety of influences, including climate, soil, religion, customs, manners, historical incidents and accidents, and so on, which ‘form the national mind’) argued that India was not a nation: it lacked a common language, a common religion, a shared tradition, a historical experience, a cohesive majority, and a defined territory, all of which he regarded as the essential ingredients of a nation. But Indian nationalists had an effective riposte. India is a country held together, in the words of Nehru, ‘by strong but invisible threads...a myth and an idea, a dream and a vision, and yet very real and present and pervasive’.

Whichever way one thinks about it, the challenge of defining India is immense. It is a land of snow peaks and tropical jungles, with twenty-two major languages (listed in the Constitution), over 20,000 distinct ‘dialects’ (including some spoken by more people than speak Swedish, Maori, or Estonian), and inhabited at the start of the third decade of the twenty-first century by 1.38 billion individuals of almost every ethnic extraction known to humanity. It has given birth to four major religions and offers a home to many more; it preaches doctrines of spirituality and wisdom, anchored in universalism and inclusivity, while still being afflicted by a caste system that visits grave disabilities upon millions of its people. It has two major classical musical traditions (Carnatic and Hindustani) to go with innumerable folk disciplines; multiple classical dance forms (Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Manipuri, Odissi, and so on) that create a rich jambalaya of diverse cultures transmitted through gurus directly mentoring select students; and by far the largest film industry in the world. In the phrase of the American poet Walt Whitman, it is vast; it contains multitudes. Is there even, one might well ask, an unchallengeable idea of the Indian nation?

And yet I have written in my book An Era of Darkness about how the notion of Bharatvarsha in the Rig Veda, of a land stretching from the Himalayas to the seas, contained the original territorial notion of India; for the bounds imposed by the mountains and the oceans created common bonds as well, making the conception of India as one civilization inhabiting a coherent territorial space and a shared history truly timeless. There are deep continuities, therefore, in the imagining of Indian nationhood, that transcend centuries of internal division.

The modern idea of India, despite the mystical influence of Tagore, and the spiritual and moral influences of Gandhiji, is a robustly secular and legal construct based upon the vision and intellect of our founding fathers

Even if ‘nationalism’ as a concept arose in Europe in the nineteenth century, as I have observed, people everywhere had a sense of belonging to communities larger than themselves: after all, the notion of the Muslim ummah, or Sankaracharya’s conception of Hinduism’s sacred geography, both imply large communities that people could identify with. In this sense it is not contradictory to argue that India is an ‘old’ nation, even though ‘nation’ is a new concept. But the nation became a salient political category in India only with the anti-colonial struggle, the case for collective self-government, and the dawn of democracy. So long as India was governed by monarchs or empires, Indians were subjects, and the question of identification was often more cultural than political. As Indians became citizens, the story changed.

I will return to this theme. For now, let me stress that the idea of India as a modern nation based on a certain conception of human rights and citizenship, vigorously backed by due process of law, and equality before law, is a relatively recent and strikingly modern idea. Earlier conceptions of India drew their inspiration from mythology and theology. The modern idea of India, despite the mystical influence of Tagore, and the spiritual and moral influences of Gandhiji, is a robustly secular and legal construct based upon the vision and intellect of our founding fathers, notably (in alphabetical order!) Ambedkar, Nehru, and Patel. The Preamble of the Constitution itself is the most eloquent enumeration of this vision. In its description of the defining traits of the Indian republic, and its conception of justice, of liberty, of equality and fraternity, it firmly proclaims that the law will be the bedrock of the national project.

To my mind, the role of liberal constitutionalism in shaping and undergirding the civic nationalism of India is the dominant strand in the broader story of the evolution and modernization of Indian society, especially over the last century. The principal task of any Constitution is to constitute: that is, to define the rules, the shared norms, values, and systems under which the state will function and the nation will evolve. Every society has an interdependent relationship with the legal systems that govern it, which is both complex and, especially in our turbulent times, continuously and vociferously contested. It is through this interplay that communities become societies, societies become civilizations, and civilizations acquire a sense of national and historical character.

The chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, Dr B. R. Ambedkar, would no doubt have argued that the constitutional roots of Indian republicanism ran deep. He remarked that some ancient Indian states were republics, notably those of the Lichhavis who ruled northern Bihar and lower Nepal in the sixth and fifth centuries bce (around the Buddha’s time), the Mallas, centred in the city of Kusinagara, and the Vajji (or Vriji) confederation, based in the city of Vaishali. Early Indian republicanism can be traced back to the independent gana sanghas, which appear to have existed between the sixth and fourth centuries bce.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, describing India at the time of Alexander the Great’s invasion in 326 bce (though he was writing two centuries later), recorded that independent and democratic republics existed in India. They seemed, however, to include a monarch or raja, and a deliberative assembly that met regularly and discussed all major state decisions. The gana sanghas had full financial, administrative, and judicial authority and elected the raja, who therefore was not a hereditary monarch. The raja reported to the assembly and, in some states, was assisted by a council of other nobles.

The oldest Indian republics varied in their constitutional arrangements. The Licchavis had a primary governing body of 7,077 heads of the most important families in the republic, while the Shakyas, Koliyas, and Mallas opened their assembly to the participation of all men, rich and poor. Villages had their own assemblies, under local chiefs called gramakas. But despite the assemblies, it is not entirely clear whether the composition and participation were truly popular, and the unequal caste duties and privileges of the members might well have affected their roles in the state, whatever be the formal importance of the institutions. Still, in the absence of hereditary monarchs with absolute powers, these states allow India to claim a standing equal to that of ancient Greece or Rome in the evolutionary history of the republic. It is no surprise, then, that while the ancient and medieval worlds largely celebrated kings and conquerors, India, while generally observing the same traditions, had other inspirations to hark back to before it entered the era of monarchs and emperors. The early Indian polities had systems, edicts, and policies, but not legislation in the sense we would understand the term today.

The British interlude was undoubtedly transformative, and it helped introduce the idea of ‘the law’ as the guiding principle of government, and therefore, implicitly (when one came into being) of the state. With the advent of the law, lawyers naturally rose to prominence in affairs of state. Since the Age of Enlightenment, many of the great people who changed the course of their nations, and the world, for good, and sometimes for the worse, have been lawyers. India was no exception: in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar, Nehru, and Patel were all lawyers (as were the principal progenitors of the subcontinent’s two nationalisms before Independence, Mahatma Gandhi and Mohammed Ali Jinnah). These men, and increasingly women—the founding fathers and mothers of the Indian republic—had the vision and the intellect to anticipate the problems and challenges that all civilizations in the modern era have had to confront. Though elected by the limited franchise permitted by the British in their rationing of democratic freedoms to Indians, the members of the Constituent Assembly, across all political lines and backgrounds, enjoyed great legitimacy, particularly those whose leadership of the freedom struggle had entailed great personal commitment and sacrifice. In the process, these distinguished lawyers found the best check-and-balance mechanism in the political and legal system created by and reflected in the book of law, the Constitution, to combat these challenges and to protect the interests of all Indians in equal measure.

Dr B. R. Ambedkar, would no doubt have argued that the constitutional roots of Indian republicanism ran deep. He remarked that some ancient Indian states were republics, notably those of the Lichhavis who ruled northern Bihar and lower Nepal

In dealing with the vast and complex realities of a subcontinent of 330 million people, politically administered in a dozen different administrative units, while seeking to integrate over 600 ‘princely states’ into the new Republic, and in devising systems and rules to embrace all of them, the founders had to acknowledge the need to produce political unity out of ethnic, religious, cultural, linguistic, and communal diversity.

As I argued nearly a quarter of a century ago in India: From Midnight to the Millennium, the most viable approach to India lies in a simple insight: the singular thing about India is that you can only speak of it in the plural. There are, in the hackneyed phrase, many Indias. Everything exists in countless variants. There is no single standard, no fixed stereotype, no ‘one way’. Throughout the first seven decades of independence, India’s pluralism was acknowledged in its constitutional and political arrangements, which encouraged a bewildering variety of social groups, religious communities, sectional interests, and far-fetched ideologies to flourish and contend. Even though India was partitioned when the British carved chunks out of it to create a homeland for its Muslims, it embraced the Muslims who remained (for decades there were more Muslims in India than in Pakistan), and sustained them through an official policy of secularism that is now bitterly challenged by its current ruling party.

In an era when most developing countries chose authoritarian models of government, claiming these were needed to promote nation- building and to steer economic development, India chose to be a multi- party democracy. And despite many ups and downs, and moments of greater or lesser stress on its democratic institutions (of which more later in this volume), India has remained a democracy—flawed, perhaps, but flourishing.

Many observers abroad have been astonished by India’s survival as a pluralist state. But India could hardly have survived as anything else. Pluralism is a reality that emerges from the very nature of the country; it is a choice made inevitable by India’s geography and reaffirmed by its history. Pluralism and inclusiveness have long marked the essence of India. India’s is a civilization that, over millennia, has offered refuge and, more importantly, religious and cultural freedom, to Jews, Parsis, several varieties of Christians, and, of course, Muslims. Jews came to Kerala centuries before Christ, with the destruction by the Babylonians of their First Temple, and they knew no persecution on Indian soil until the Portuguese arrived in the sixteenth century to inflict it. Christianity arrived on Indian soil with St Thomas the Apostle (the Doubting Thomas of Biblical lore), who came to the Kerala coast some time before 52 ce and was welcomed on shore, if legend is to be believed, by a flute-playing Jewish girl. He made many converts, so there are Indians today whose ancestors were Christian well before any Europeans discovered Christianity.

Islam is portrayed by some in the North as a religion of invaders who pillaged and conquered, but in Kerala, where Islam came through traders, travellers, and missionaries rather than by the sword, a South Indian king was so impressed by the message of the Prophet that he travelled to Arabia to meet the great teacher himself. The king, Cheraman Perumal, perished in the attempt, but the Kerala coconuts he took with him have sprouted trees that flourish to this day on the southern coast of Oman. Indeed, the Zamorin of Calicut was so impressed by the seafaring skills of the Muslim community (epitomized in the famed and fearless Kunjali Marikkars) that he issued a decree obliging each fisherman’s family to bring up one son as a Muslim to man his all-Muslim navy!

India’s heritage of diversity means that in the Kolkata neighbourhood where I lived during my high school years, the wail of the muezzin calling the Islamic faithful to prayer routinely blended with the chant of mantras and the tinkling of bells at the local Shiva temple, accompanied by the Sikh gurdwara’s reading of verses from the Guru Granth Sahib, with St. Paul’s Cathedral just around the corner. Today, I represent in the national parliament the constituency of Thiruvananthapuram, the capital of Kerala, where the gleaming white dome of the Palayam Juma Masjid stands diagonally across from the lofty spires of St Joseph’s Cathedral, and just around the corner from both, abutting the mosque, is one of the city’s oldest temples, consecrated to Lord Ganesha. My experiences and encounters in my constituency remind me daily that India is home to more Christians than Australia and nearly as many Muslims as Pakistan.

That is the India I lay claim to.

Reprinted with the author's permission. Aleph Book Company released the book 1 November, 2020.

Prolific author, Indian member of parliament from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala (re-elected for a fourth successive term in June 2024), and former Minister of State for External Affairs, Shashi Tharoor has also served as a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Under-Secretary-General for Communications and Public Information, and as a senior advisor to the UN Secretary-General. He is the author, most recently, of Ambedkar: A Life (Aleph Book Company, 2022). His website is www.tharoor.in

Post a comment

- HOME

- BUSINESS

- DEVELOPMENT

- ENERGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- HEALTH

- INFORMATION

- POLITICS

- SECURITY

- SHIPPING

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- TRENDS

Long term impact of Gaza attack on Israel

Consequences of Palestinian conflict and finger-pointing in the blame game ... See world opinion

Curse of curation

PR-speak is turning our conversations into outright gibberish... more…